This post introduces a sentience-centered approach to animal advocates' cause prioritization, arguing that our moral consideration should extend (only) to all sentient individuals. It explains how quantifying sentience & welfare helps with decision-making across species interventions, and offers examples of how this framework can guide animal advocacy efforts and identifies practical and emerging methods to assess animal wellbeing. It aims to nudge animal advocates towards a sentience-focused welfarist approach to their work, and to clarify and increase the advocates' understanding of this perspective.

Definitions

Sentience

"If something is sentient, it has the capacity to have positive or negative experiences, to be aware of sensations. We generally think of dogs as sentient and rocks as non-sentient: it isn’t 'like' anything to be a rock. Being sentient is different from being alive: after damage to certain parts of its nervous system, a being can cease to be a subject of experience, even if its body is alive— it can be alive and non-sentient. Many living things are likely non-sentient, perhaps including bacteria or plants. Sentience seems to require a certain type of physical structure/organization to arise, such as a functioning nervous system.

Why Sentience Matters: Sentience is morally significant because only sentient beings can be harmed or benefited. Unlike non-sentient objects, which can be 'damaged' but don’t have positive or negative experiences, sentient beings can suffer or enjoy their experiences. Sentient beings can have intrinsic interests of their own, whereas a statue does not have any interests, such as in avoiding erosion or rust." -Animal Ethics

Suffering and Enjoyment

"The terms ‘suffering’ and ‘enjoyment’ can be misleading if taken too narrowly. In the context of sentience, they refer to any kind of negative or positive experience, not just physical sensations. While sentience doesn’t require advanced cognition, many sentient beings have mental states— experiences that arise internally. So, sentience can be understood as the capacity for any kind of suffering or enjoyment." -Animal Ethics

Welfare

While “sentience” is the capacity to have positive or negative subjective experiences at all, Wild Animal Initiative (WAI) defines “welfare” as “the aggregate quality of subjective mental experiences, at a given point in time or over a given period of time”. Notably, WAI’s definition focuses exclusively on mental states, leaving open the possibility for a sentient being to be in poor physical health or in an unnatural environment while still having positive subjective welfare.

Net Negative Lives

A reason to quantify welfare is to assess whether an animal’s life is net-negative, meaning a life that contains more suffering than wellbeing. Net-negative lives are, by definition, generally understood to be not worth living; if an animal is expected to live a net-negative life, it may be ethical to prevent its existence in the first place (e.g. some factory farmed animals) or to euthanize an animal (e.g. an animal with an incurable, painful disease).

QALYs

When deciding where to allocate scarce resources like donor funds, an organization may ask the question: “which animals need the most help right now?”. This question requires quantifiable estimates of welfare for the purpose of comparison and decision-making, or prioritization. Global health organizations and governments often compare human health interventions using a measure called QALYs, or Quality-Adjusted Life Years.

QALYs allow us to compare not just the number of lives saved, nor how many years of life saved (e.g. saving a young vs old person), but even allows us to compare interventions that improve someone’s quality of life without extending their lifespan (e.g. by restoring someone’s eyesight, or treating depression). While it isn’t feasible to get an absolutely precise/objective measure of someone’s subjective wellbeing, QALYs allow us to compare interventions that might otherwise seem like “apples and oranges” by introducing a common measure.

Why Quantify Welfare? Comparing Across Species

What about comparing interventions across species, e.g. when choosing whether to advocate for the wellbeing of farmed chickens, farmed fish, or farmed worms?

Individuals within and between species can have different levels of sentience, allowing some to have more intense subjective experiences— for example, a human and a tarantula may both be sentient while having a very different capacity of maximal positive or negative welfare. The amount of welfare an individual is capable of realizing at one time is called its “welfare range”.

Quantifying welfare ranges can help us make decisions about which individuals to help and how, especially when we need to triage limited resources (which is ~always the case in a cash-bottlenecked cause area like animal welfare), or when two animals have competing interests requiring tradeoffs (e.g. in trophic interactions).

Charity Entrepreneurship, an organization which conducts rigorous research and incubates high-impact animal welfare & global health charities, developed its a system called SADs (Suffering-Adjusted Days), which functions like QALYs to compare the effectiveness of animal welfare interventions across species. SADs measure the number of days spent in pain with adjustments for intensity of pain, the relative sentience of the animal, and the welfare range of the animal. SADs incorporate the Welfare Footprint Framework, a universal animal welfare metric which enables us to quantify an animal’s subjective pain or pleasure based on its intensity, duration, and other information.

When we have limited resources, we have to prioritize. And prioritizing between groups of animals requires us to compare— to the best of our ability— our best estimates of an animals’ subjective welfare.

Number of Animals vs Days Spent Suffering

Looking at the projected number of farmed animals in 2033, insects are expected to make up a far greater number of total animals farmed than all other groups combined.

However, this is due in part to how short insect lives are on average. When we look at the total number of animals alive at any given time, insects will make up closer to only a third of total farmed animals. This means that insects will not represent that much more of the total time spent suffering than fishes or shrimps, despite having a far greater number of individuals killed per year.

A single fish’s lifespan will last for many insect lifetimes, so how we calculate total suffering is important. This begs the question about how should we measure suffering: by number of individuals, or the total time spent suffering?

Time spent suffering is also impacted, of course, by the quality of life experienced on any given day. On factory farms, this is often quite controlled and predictable. When we look at the painful lives of broiler chickens, the number of days spent suffering varying levels of pain is affected by how fast this breed of chicken grows. A chicken that grows slower may spend more total time alive, but less total time in pain.

In order to quantify the total time spent in varying degrees of pain, we must identify what makes a unit of time higher- or lower-welfare. We likely also care about whether a day spent in pain matters more for a chicken than an insect, or a human than a chicken. How do we quantify sentience and welfare in practice?

How might we quantify sentience/Welfare in practice?

Welfare Range Table & Cognitive Proxies

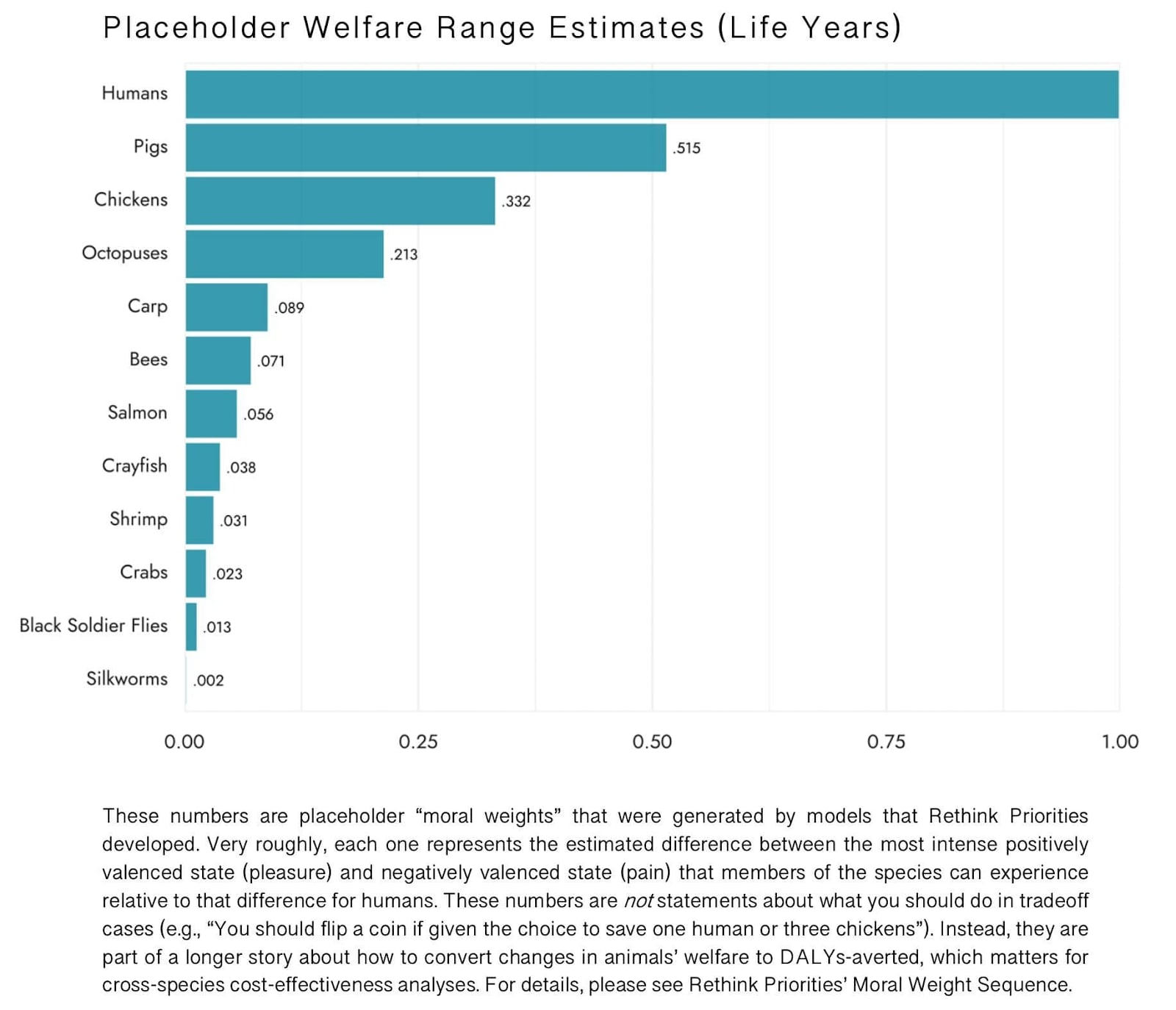

One attempt at estimating various species’ welfare ranges is Rethink Priorities’ Welfare Range Table. A key component of the welfare range table are the Cognitive Proxies, a set of cognitive and physiological traits used as proxies to help estimate the depth, complexity, and intensity of each species’ cognitive experiences.

You can see on the Cognitive Proxies table that each species is rated for the probable presence or absences of 35 cognitive capacities based on the available evidence. This project represents an early framework for how we might go about estimating the welfare range and/or relative sentience of various species.

The result is the beginning of a framework which could help compare the cost effectiveness of DALYs averted across different species.

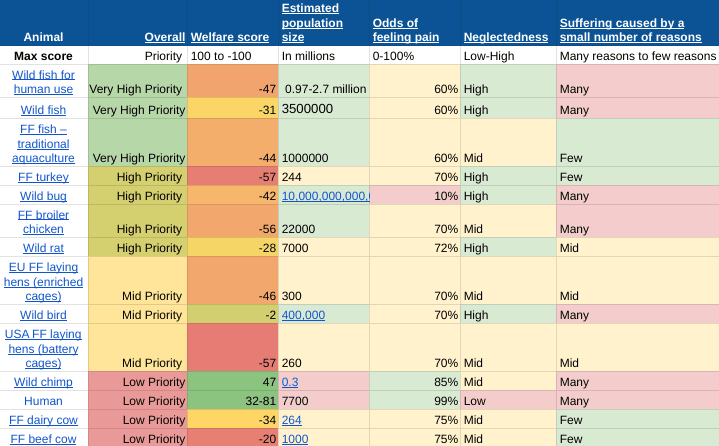

Prioritization of populations

Welfare Range estimates can also help us identify animal groups that are more neglected/more urgently in need of help. For example, when considering what kinds of charities to incubate, Charity Entrepreneurship engages in a rigorous research process to identify neglected animal welfare cause areas. Their research incorporates estimates of welfare ranges and experienced welfare, as well as population sizes and traits like tractability and neglectedness, to estimate which animal groups may be most positively impacted by the incubation of a new organization focused on their welfare. A small part of that research process looks something like this:

Simpler Proxies and Outstanding Issues

While it’s difficult to say exactly what is going on in another being’s mental state, in some cases, it is feasible to approximate animal welfare based on accessible proxies that are readily detectable by humans. For some animals, we can estimate wellbeing based on expressive behaviors, such as play or facial expressions. Some methodologies suggest using animal vocalizations, which can vary with emotional state.

Of course, measuring animal welfare still presents serious methodological challenges. Behavioral tests, physiological indicators like cortisol, and preference studies offer insight, but all have limitations. For example, stress hormones can spike during both negative and positive events, and some animals may prefer familiar conditions even if they're worse. Despite these limitations, carefully designed research can still provide valuable estimates of wellbeing.

While there are still many outstanding research questions in measuring animal welfare, making progress in this field will reveal opportunities for welfare gains. This is more than just a scientific exercise: as our tools for welfare assessment improve, so too will our ability to make responsible, evidence-based decisions to help animals in need.

The relevance of sentience in moral consideration

Moral Patienthood

When making decisions about the world, we should take into consideration the interests of all moral patients affected. Moral patienthood is the condition of deserving moral consideration. Many welfarists believe that sentience is the arbiter of moral patienthood, since non-sentient objects cannot have welfare or interests. Objects can have instrumental value— for example, the Mona Lisa may bring happiness or other worthy things to sentient humans, but the Mona Lisa does not have a personal interest in surviving a fire. A welfarist may say that the Mona Lisa ceases to have value if there are no longer any sentient beings around to enjoy it— it has no intrinsic value, just instrumental value to the sentient beings capable of having interests/welfare.

Moral Circle Expansion

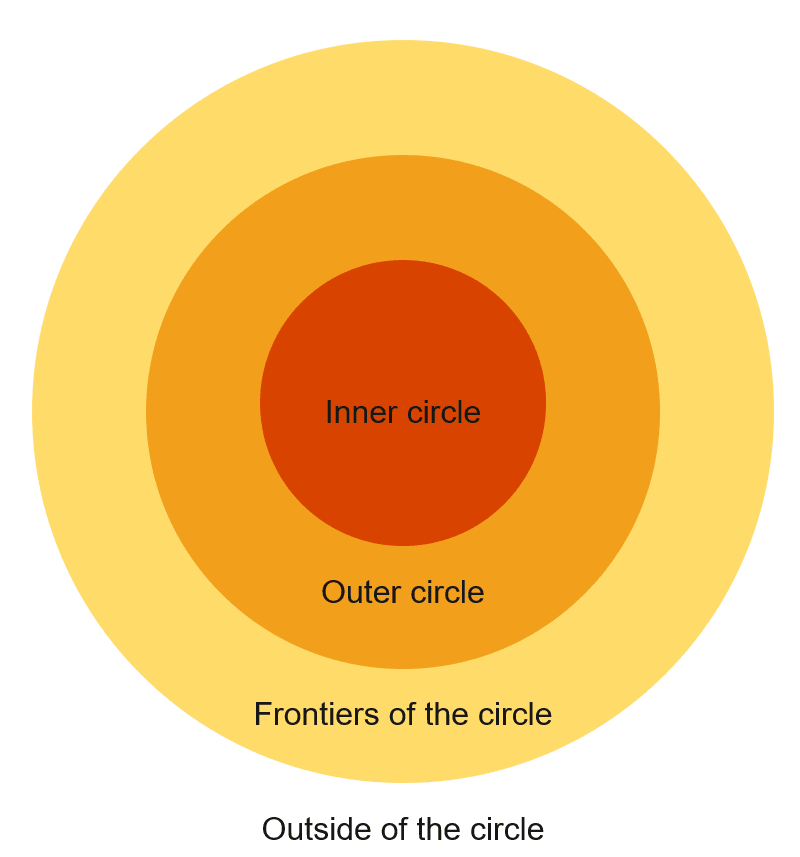

If the Mona Lisa does not have intrinsic moral patienthood, it can be said to lie outside of the moral circle— outside the boundaries of what gets moral intrinsic consideration for its own sake. That which is inside the moral circle, such as humans or cats, have moral patienthood, meaning that their interests deserve intrinsic moral consideration. Some conceptualizations of the moral circle have “tiered” levels of moral consideration, as illustrated in Sentience Institute’s “Our Perspective”.

To some extent, human history has seen a progressive expansion of the moral circle, coming to include humans from outside one’s tribe or identity group as well as non-human animals. And while this is a good thing, most of us wouldn’t want the moral circle to expand indefinitely: including every grain of sand on every planet for intrinsic moral consideration doesn’t seem sensible.

So where does one draw the boundary? A sentience-focused welfarist might choose to draw their circle’s boundary along the lines of sentience: what is not sentient is outside the circle. To account for uncertainty, we might give some moral consideration to beings that are probably not sentient.

(A note on moral circle “tiers” and speciesism: the organization Animal Ethics argues that all sentient beings belong within the moral circle and deserve full moral consideration. While it is reasonable to prioritize certain interests based on differences in sentience—e.g. how intensely they can suffer—this is not a justification for placing nonhuman animals in a lower tier of moral importance simply because of their species. Any differences in moral weight must be grounded in relevant experiential capacities, not species identity.)

Focusing on Sentient Individuals

In The Relevance of Sentience, Animal Ethics describes some implications of focusing on sentience. Since sentience requires the ability to have experiences, a sentience-focused welfare perspective places intrinsic value/moral consideration on individuals and their experiences; all else has instrumental value.

This means we should not include in our moral circle (though these may still have instrumental value, and may still be worth spending resources to preserve despite not being moral patients):

- All Living Beings

- “Biocentrism is an environmentalist view that claims we should give moral consideration to all living things, including plants and other non-sentient beings. This text explains why sentience, rather than being merely alive, is what ultimately matters. It also explains why, in reality, the biocentrist view is a speciesist view, as it makes exceptions for instances of harm to humans but not for instances of harm to animals.”

- Ecosystems

- “Another environmentalist view claims that we should give moral consideration to entire ecosystems rather than to sentient animals. This text explains why we should care about individuals, rather than systems or other abstract entities, such as ecosystems or species, because they are not sentient beings. It also explains why, as with biocentrism, the moral primacy of ecosystems is not consistently maintained when human beings are subjected to harm, yet is defended when nonhuman animals are harmed, which makes it inconsistent and biased.”

- Species (instead of individuals within that species)

- “Another position which is widespread among environmentalists is the view that animals and plants matter as long as they are “exemplars”, that is, members of certain species, whether they are sentient or not. According to this view a living thing should be conserved if their species has scarce numbers, but not otherwise. Confining and killing animals are considered justified methods to achieve this, even when it means killing animals to preserve a plant species. This text explains how this view fails to consider that which is morally relevant – sentience. What is important is the interests of sentient individuals, and not the number of individuals in a group.”

What’s more, in this view, sentience is the only requirement for moral consideration, not traits like specific intellectual capacities or a special relationship to humans, for these traits are irrelevant to whether or not a subject can experience harm or benefit.

Conclusion

Placing sentience at the center of moral consideration encourages us to focus on the lived experiences of individuals—those who can be harmed or helped. It challenges us to prioritize not based on species identity, ecological symbolism, or abstract groupings, but on the capacity to experience suffering or wellbeing. As we continue to develop better tools to quantify welfare and compare across species, we move closer to making more compassionate, evidence-based decisions about how to allocate our limited resources. Whether or not we adopt every aspect of this perspective, understanding it allows us to engage more meaningfully with the ethical foundations behind modern animal advocacy and effective altruism.